Leadville Trail 100 Mile Run:

100 Mile # 4

Date:

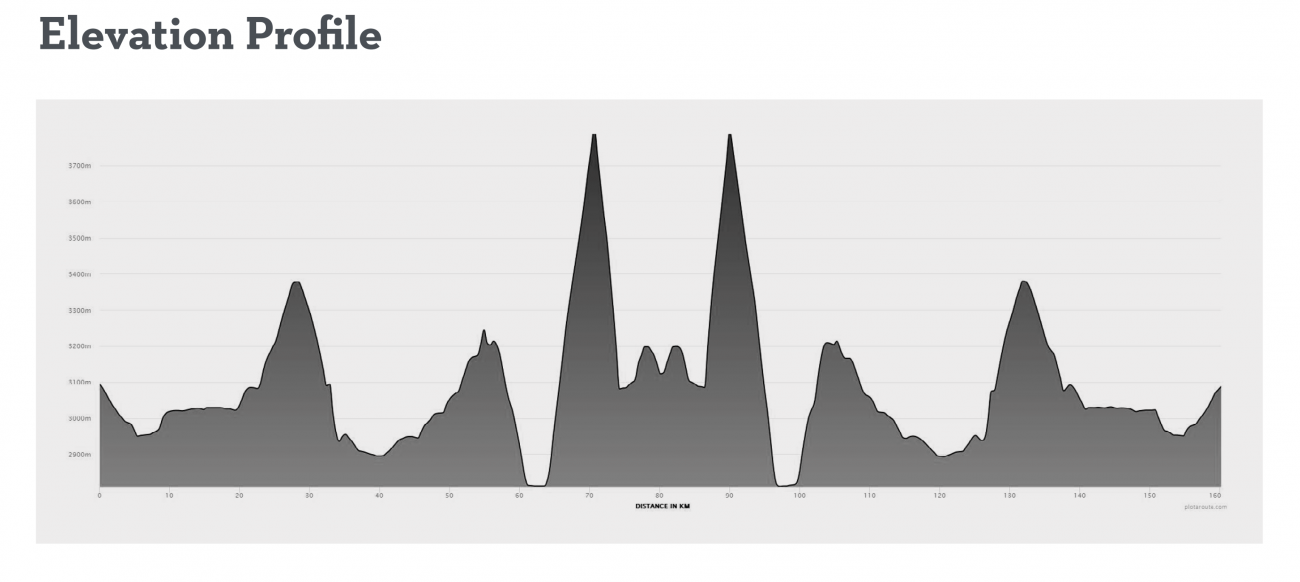

August 20, 2022The Leadville 100 miler. The granddaddy of all endurance trail running events. The renowned “Race Across the Sky” that takes runners on an epic out and back journey across the biggest, baddest, and toughest mountains that Colorado has to offer. 100 miles/160km. 4800 metres elevation gain. A course low point of 2800 metres and a course high point of 3820 metres (i.e. Hope Pass). The race where legends are created and limits are tested. Where altitude clashes with attitude. I’d entered the Leadville 100 in 2019 and had planned to do it in 2020 but we all know how that year turned out. Events folded and international travel came to a halt. For two years, I had the Leadville 100 at the back of my mind. But it wasn’t until the start of this year that I tentatively booked flights to Denver, Colorado. Even then, there was no guarantee. But as travel restrictions loosened, my hopes began to rise. And so I began to train. Train like I’ve never trained before! This race scared me. I knew this race was on the edge of my abilities. I’d accrued experience, stamina, and mental toughness over the years. But this was really pushing my engine’s limit (i.e. cardiorespiratory capacity). I knew I could finish a 100 miler. But the Leadville 100 had to be finished within 30 hours. At first, 4800 metres elevation gain at an 11 min/km pace doesn’t sound too daunting. But combine that with 100 miles of running at 3000 metres above sea level and finishing within 30 hours becomes extremely challenging and very intimidating. Christchurch is only 20 metres above sea level. The start/finish line at Leadville is 3094 metres above sea level. I was a “flatlander” as locals called me. And flatlanders (e.g. those from California), had reduced odds of finishing races at altitude compared to races at sea level. In fact, I’d argue that so did everyone else! Leadville had a historically very high DNF rate of 50%. Because of all of the above, this race had me on edge. I was borderline obsessive. My training went up another level. The only time I had trained in similar vein was for my fist Ironman. That event also scared me. I feared I’d drown so I kept swimming to survive. I wasn’t afraid of dying in the Leadville 100 (it’s actually quite hard to die whilst running). But I feared the DNF. I’d never DNF in my life. I had a clean slate. Whatever I started, I finished and I prided myself in that. It became who I was. I was a finisher. And so, after I completed the Southern Lakes Ultra stage race in February (264km/7days), I started to train properly. Previously I’d maintained my fitness by what I call ‘event hopping’ (hopping from one event to the next without much training in between). I still did some events. Notably the Mt Oxford Odyssey Mountain Marathon (May – hill focus), the Selwyn Marathon (June – flat fast focus), and the Wuu-2k 62km Ultra (July – hill focus) in addition to the Leadville Training Camp in June. But this time, I started running more consistently between events. When I say consistent, I mean running at least 3 days a week on a weekly basis over 5-6 months (usually I’d run 1-2 times a week in the hills). I ran at least 3 times a week and each running session had a focus. One running session focused on flat fast running (i.e. Hagley Park), another session focused on hills (i.e. the Port Hills), a third session was my long run (4-6 hours in the hills), and the final session was a recovery run / run to keep my dogs under control if they weren’t already tired with all of the above. I also managed to maintain my Ironman cross training (biking, swimming, and swim/bike/run transitions), resistance training, and flexibility training throughout all of this so life became quite busy! At the peak of my training, I was doing up to 14 training sessions a week over a couple of months. I even did a few sessions of altitude training at Vertex Altitude Christchurch leading up to my NZ departure (thanks!). Although I struggled to begin with, my pace, endurance, and ability to recover significantly improved. Prior to leaving NZ, I studied the whole Leadville course like I was at medical school again. I read blogs/books about the run. I watched YouTube videos of previous participants’ experiences. I pulled out my old Sports Physiology text book and familiarised myself with the effects of altitude on the body and altitude adaptations over time. I knew where all the aid stations were and the corresponding cut off times required for a successful sub-30-hour finish. When we (Dr Stanley and I) arrived into Leadville (via Denver) 2 weeks before the race, we walked/ran a few key segments of the course as training runs. My wife Courtney arrived a week later as my lone support crew and pacer for the last 37km of the race from Outward Bound to the finish. I’d never been this prepared for a race in my whole life! Despite all of the above, the race still scared me. There were many doubts but I knew that I was as prepared as I could be. I told myself that doubts were a good thing. Doubts mean that you’re extending and challenging yourself. According to ‘Leadville Trail 100: History of the Leadville Trail 100 Mile Running Race’, only 6 other New Zealanders have successfully completed the Leadville 100 since its inception in 1983. Dr Stanley and I were hoping to make that 8 finishers.

Main street in Leadville (10 152 feet / 3 094 metres)

As I walked towards the start line at 6th and Harrison just before 4am, it’s fresh but not chillingly cold. I say goodbye to my wife and wish Dr Stanley the best of luck. Today, we would be running our own races. He heads to the front of the group and I settle in towards the back. I’ve got 30 hours to complete this. No point getting caught up in the fast-paced energy at the start of the pack. Shuffling around towards the back of the pack, I take a moment to reflect. The pre-race briefing we had yesterday at the high school football field is still fresh in my mind. “Motivation will get you to the start line. But only total commitment will get you to the finish. Dig Deep. Commit. Don’t quit. Inside each and everyone of you is this inexhaustible well of grit, guts, and determination. You’re better than you think you are! You can do more than you think you can! At 4am tomorrow, you will meet the truth.” It’s not long to go before the start and they’re playing The Star-Spangled Banner. I tighten up my shoe laces and then look beyond the start line. Time to stare truth in the face. This is it. Am I good enough? There was the customary starter’s gun but also a final gun that sounded at the finish line at 30hr:00min:00sec. After this, no additional runners officially finished the race. The race was over, done, caput. Between the bang (shot gun blast) and the buckle (sub-30-hour finisher’s belt buckle), it really was up to me. I knew I needed the perfect race. I had a plan. I had a strategy. Thirty hours of continuous effort. One hit. No sleep. I took a slow deep breath of the thinnest air of the land and on the sound of the old double 12-gauge shotgun, I crossed the start line with 700 other runners.

At the Leadville 100 start line with Dr Andrew Stanley (right)

After the initial excitement of the start line, the atmosphere becomes serious as runners focus on the task ahead. It’s dark and I’m running down a dirt road called The Boulevard. In its pomp, The Boulevard was a well-manicured route heading west of Leadville to Soda Springs (apparently ‘no road was smoother than The Boulevard’). But nowadays, The Boulevard is the ultra runner’s devil in disguise. Being dead straight and still relatively smooth, The Boulevard has a generous downhill gradient that is inappreciable in the dark and hence it is very easy to run 6min/km and TOO FAST this early in the run. I hold back my pace and restrain the ego. Let them pass. You will pass them later. My goal for Leadville was simply to finish. My plan was to take this race as deep as I needed to. Instead of ‘dig deep’ as per the famed race motto, my intention was to ‘fight deep’. For me the Leadville 100 was akin to a boxing heavy weight KO specialist and I was the aspiring underdog hoping to take on the storied champion in his own back yard. The Leadville 100 had a historical ‘knock out / DNF’ rate of 50% and had KO’ed far more reputable and cardiovascular gifted athletes than myself. If Leadville was the champion, then the altitude it fought on was king. The partial pressure of oxygen in the air at Leadville was between 97 and 110 mmHg (it’s 159 mmHg at sea level and 48 mmHg at Mt Everest) i.e. there’s significantly less oxygen in the air at Leadville than at sea level. I had to respect altitude physiology and know my own cardiovascular limitations. Know thyself. Know thy enemy. My understanding was that one of the reasons for the high DNF rate was that runners went out too fast too early to keep within the hard cut off times – going for the early KO as such. It seems that when you hit the wall at altitude, it’s a lot more significant and takes a lot longer to recover from compared to hitting the wall at sea level (potentially it’s even terminal). My altitude physiology had taught me that at 3000 metres above sea level, I was unlikely to replicate my sea level 100 miler personal best time of 27 hr 18 min. Not impossible, but realistically if I were to equal my sea level PB performance, then that would be considered an exceptional effort rather than the norm. I therefore realised that I needed to be comfortable with being close to the cut off times. Cut offs were to serve as a motivator but were not to be feared. Also, the “big silver buckle” finish of sub 25 hours was not even considered. Potentially this could be a goal for the future. But at my first attempt at Leadville, a sub-25-hour finish would surely have been a suicide mission. One where I would’ve probably won the early rounds only to be swiftly dismantled in the middle to late sections of the race. Therefore, sub 30 hours was my goal. Under 30 hours was achievable. Nothing more would suffice. If I had to take it to 29:59:59, then so be it. A finish was a finish. So I intended to dig deep. Fight deep. I needed to go toe to toe for the full 12 rounds against one of the biggest, baddest, toughest knock out artists out there if I was to stand any chance. Employ my lengthiest and busiest jab ever to keep the “Dreadville slugger” at bay. Run within myself whilst still run within the hard cut off times. Don’t stop when I’m tired. Stop when 12 rounds are finished. That was my plan. Skirting around Turquoise Lake, the sun begins to rise and I’m feeling good. I leave the first aid station at Mayqueen in 2hr 34 mins. Exactly where I want to be. Twenty kilometres with minimal exertion. One hour and 10 mins ahead of the cut off time. First round to Molloy. I quickly top up my water and walk out with a handful of food. The road out of Mayqueen is a runnable gradual incline but at this stage its more important to get my calorie count up for the fight ahead rather than run. I switch gears to walking and leave Mayqueen with my mouth and hands full of food.

Heading down West 6th Street after an early 4am start

In Leadville, you need a few gears. You need a running gear for the undulating technical, a running gear for the flat roads, a walking/hiking gear for the ups, and a downhill scrambling gear for the descents. You also need to transition reasonably well between gears and it pays to have a ‘shuffle’ for the latter part of the race. After running exclusively for most of 2.5 hours, it was nice to transition into a purposeful walk (not a stroll, a purposeful walk – at least 11min/km an hour). Heading into the Colorado Trail you encounter the gushing white of rivers and the green hues of the forest. It’s quite rocky underfoot but this is nature. It’s nice to take the trail less travelled at times. True nature is raw and unaccommodating and I like that. Coming onto Hagerman Pass Road, we’re back onto runnable dirt road again. Some start to run but I resist the urge. The road’s incline gradient is not worth the return at this point of the race. I keep a steady walking pace and keep eating whilst I can. We then turn off Hagerman Pass Road and onto a steeper jeep road which marks the first significant climb of the Leadville 100 – going up Sugarloaf Pass. After about 60 minutes of continuous up, it’s a rather steep and jarring descent down the pass along prominent powerlines (hence this tortuous climb during the inbound section is affectionally known as ‘Powerline’). I’m careful not to push too hard in order to save my quads. But I also want to work with gravity to keep pace with the cut offs. After a good portion of downhill running, its back onto undulating road again. If you want to finish a race like Leadville, anything that is reasonably flat and runnable HAS to be run. I maintain a good honest running pace along the road with a few purposeful walks for the sharp inclines. I manage to get through the next aid station at Outward Bound in a cumulative time of 5 hrs and 5 mins, 55 mins ahead of the cut off time. Another round to Molloy. There are large marquees everywhere and the aid station is bustling with runners and their crew. The music is pumping and it feels a bit like a party atmosphere. However, not having any crew here (or any innate desire to party), I grab some more food and box on. I know Courtney is 5.5km away at an unofficial crew location called Pipeline so that keeps me focused. And that’s where I head.

Some of the scenery near the Mayqueen trailhead

To finish the Leadville 100 in under 30 hours, this requires a 11min/km pace. However, what some fail to consider in their plans is that there are 13 aid stations on the course. If you spend a paltry 5 minutes at each aid station, that is about an hour of time. An hour which none of the pace calculators factor for! Though others with larger cardiorespiratory engines could afford to spend more time at aid stations, I could ill afford to dwindle an hour. If I wished to finish, I needed to ‘go through’ the vast majority of aid stations and be very efficient at the aid stations I’d preselected to stop at. I’d essentially ‘gone through’ Mayqueen and Outward Bound. The next section of the course after Outward Bound could be very exposed to the sun and it was approaching 10am. Being 3000 metres above sea level meant that you were closer to the sun, so the sun had greater potential to cause havoc. Though it was currently overcast and the weather forecast was predicting an 80% chance of rainfall (and thunderstorms) by midday, I refused to chance it. Heat was my enemy. Not controlling for heat often leads to an increased heart rate (and ensuing rate of perceived exertion) and more blood being directed to your peripheries (to cool) rather than to your muscles to run. My next stop at Pipeline was therefore a dedicated ‘cooling stop’ with the primary focus being getting fresh ice-cold drinks to help manage the heat of the day. When I caught up with Courtney at Pipeline, I allowed myself 2 minutes to do what I needed to do. Courtney was rather chipper but it didn’t take her long to realise I wasn’t as jovial. I guess running 42km under pressure can do that. “Let’s go. I want to get in and out of here” I barked. I dropped off my head lamp, picked up some ice-cold Tailwind and water, stuffed some lollies into my pack, popped on my sunglasses, and I was out of there. “I’ll see you later around 1am” I said as I started running again. Though I thanked Courtney as I left, I imagine she may have been quite dissatisfied with the experience. Here she is waiting for ‘hours’ to ensure she doesn’t miss me and I show up and leave within 2 minutes whilst imparting my grumpiness. Would she even come back? Something tells me that I’m unlikely to be a box of birds, God’s gift to women, or any other equivalent in another 15 hours. She did mention that she heard some runners had pulled out at Outward Bound or were struggling to make the cut off time there. I struggled to comprehend that this early in the race. It felt like I had sacrificed so much to get here. How could people be so off their pacing this early in the piece? How could anyone throw in the towel this early into a 100 miler? Maybe it was because I sacrificed so much family time, work time, and finances that I had so much riding on this? Maybe the ‘months’ of training and preparation were driving me? In a 100 miler, if you fail to prepare, you prepare to fail. I’d done all the preparation possible. I just had to keep going deeper into the fight.

Arriving into Twin Lakes aid station (60km)

I ran the majority to the next aid station at Half Pipe (47km). Another points victory to Molloy. I briefly filled up my water and pushed through again. As I walked out of the aid station, I forced another chocolate bar down me. I’d been on my feet for more than 6 hours now and was one hour and 25 minutes ahead of the cut off time and well placed. It was somewhere in the section between Half Pipe and Twin Lakes outbound that the course started to throw a few punches of its own. In ultra running, if it’s going well, be prepared as things can quickly change. Somewhere around the 50km mark whilst climbing up Mt Elbert, I started to feel the cumulative effects of my concerted efforts. For the first time in a while, people started passing me. I tried to cling on to people as they passed me but to no avail. I had entered Struggleville. After winning the early rounds, it was like I had poked the bear and Leadville was swinging. I began to feel a bit flustered, hot, and light headed. The good thing about being a doctor is that more often than not, you can reassure yourself that feeling terrible doesn’t correspond with an underlying medical emergency. I knew this ‘low’ was just a normal phase of long distance running. I sometimes wonder how much of this is psychologically mediated with the mind priming the body for the bigger fight ahead. The Hope Pass double is coming up. Do you really want to go through with this? I’m going to slow you down so you can carefully consider your options. Like any life phase, you just got to hang in there. Roll with the punches as such. Sip and nibble. Slow down a bit. Nibble and sip. By the time I managed to get to the top of the climb (recognisable by a grove of Aspen trees), it was a matter of letting gravity do the work for you on the downhill and things seemed to get better. Despite being a little worse for wear, I arrived into the Twin Lakes aid station in reasonable spirits. The support was really uplifting. Gazebos lined the streets and cheers rang through the town. For a moment I forget about all my struggles. I chose not to stay long at Twin Lakes. Just topped up my drinks again, picked up my head lamp in preparation for the dark, and walked out eating a cup of mashed potatoes and potato chips. I left Twin Lakes at 12.30pm, one hour ahead of the cut off time. It wasn’t long before everything became quiet and I was listening to my own breathing again. Looking out into the distance I could see Hope Pass. The saddle between two mountain peaks. It just stared at me. The truth. Its brow frowned like a street smart slugger. “You want it, come and get it!” it taunted. Was that lightening I saw in the background? The forecast rain and thunderstorms had yet to arrive. I don’t know. Onward.

A multitude of support crew at Twin Lakes Village

Leaving Twin Lakes and heading outbound towards Hope Pass in the distance

Hope Pass has been described as the heart and soul of Leadville. The pinnacle of the Leadville 100. It’s nearly 1000 metres to the top hitting the course high point of 3820m. Runners reach the summit not only once, but TWICE on an out and back trek. One can expect to be gasping for breath, light headed +/- have a headache, and nauseous +/- vomiting. It could be sunny and peaceful up top or equally blowing a gale with rain/hail and a small risk of death by lightening. During the inaugural running of the event in 1983, the medical director at the time declared “someone may die in this race” due to the extreme altitude. Though this may not be palatable for some, acceptance of the above appears to be a prerequisite to finishing the Leadville 100. As I cross the shin high river crossing heading towards Hope Pass, this signals the end of any comfort for my foreseeable future. Going up Hope Pass is a slow and steady process. It’s an average 15-degree incline gradient over 6 km so you’re climbing for a couple of hours. As much as I try to enjoy the lush forest around me, I’m really reduced to concentrating on my breathing. Breathe in through the nose. Gasp. And out through the mouth. The hypoxic struggle also gives you the opportunity to channel your inner Miyagi. Sun is warm. Grass is green John san. There are some athletes with some massive engines on display as they power hike past me but I’m unperturbed. The fact I’m ahead of them at this stage of the race tells me I must be doing something right. I maintain a slow and steady pace throughout such that I don’t need to stop. As I pass the ‘Hopeless aid station’ about a kilometre from the top of the pass, it’s tempting to join the llamas (who have hauled all the supplies to this aid station) resting in the field. But I know I need to keeping boxing on to maintain momentum. I grab a cup of noodles and push onwards whilst attempting to eat on the move. A collection of multi coloured prayer flags marks the top of Hope Pass. The light drizzle which started above the tree line has cleared so it is remarkably sunny and quite still at the top. However, I’m feeling quite breathless and my head feels vacant so I’m not too keen to stick around in this thin air. I roll over the top and let my momentum and gravity take me most of the way down the other side. Just before Winfield, I come across Dr Stanley running behind a small train of runners heading back inbound. To tired to talk, we give each other a high five as we pass each other. The pressure is still on and we know we’re in the thick of the fight now. I arrive at Winfield at 4.40pm which is the same time I was hoping to leave so I’m a touch behind schedule. Winfield is the turn around point and marks the half way stage of the race. Although I’ve tried to keep as much fuel in the tank as possible, Hope Pass has really taken it out of me. After 80km of nonstop relentless forward momentum, I feel compelled to plonk my sorry carcass onto a chair for the first time. F*** that was hard. Now I have to turn around and do it all over again! I know I need a pick me up of some type so I grab a cup of chips and pretzels as I sink deeper into the chair. Suffice to say, I’m feeling pretty buggered and the sensation of discomfort is increasing. As I try to gather my thoughts, the words of Ken Chlouber (Leadville 100 co-creator) come into my mind. “You’re going to be dealing with a lot of pain. Make pain your fuel! Make pain your friend and you’ll never be alone!” Bugger that. I pop a couple of paracetamols. It’s too early to embrace pain. Ding ding ding. I can hear a bell ringing in the distance. I swallow a Leppin Squeezy and pick myself up off the canvas. I leave Winfield at 4.50pm with a cumulative time of 12 hours and 50 mins. One hour and 10 minutes ahead of the cut off time. Ready to battle with Hope Pass again.

Just leaving Hopeless aid station and heading towards the top of Hope Pass

Prayer flags on top of Hope Pass

Leaving Winfield, a face can portray a thousand words and a story. It’s during this part of the run that I pass a lot of competitors heading outbound to Winfield as I head inbound back towards Twin Lakes. At some point you do the maths in your head and you realise that there’s no way these outbound runners are going to make the 14-hour cut off at Winfield. I’ve been running out of Winfield for 50 mins now. You won’t make the cut off in 20 mins. It’s like a slow transition of faces from calm, focussed, determined, pressured, hurried, and desperate eventually ending in disbelief, anger, sadness, and then acceptance. No words are spoken or required. Some put on a braver face than others but their body language reveals the truth. A lot of races ended in that short single trail heading out to Winfield. When you run, sensations are amplified. You feel more. Though you may try to ignore these sensations or shield yourself, the reality is that we are all connected somewhat on the trail. You can feel ‘disappointment’. You can sympathise with hopes shattered. At some point the run becomes bigger than just you. At some point you realise that you HAVE to complete this thing. Not just for you, but for others. For those that can’t or won’t. For those who don’t have the opportunity. For all those whose race has ended prematurely. You begin to appreciate that you have more people vouching for you in your corner than you can ever imagine. And for that reason, you have to keep fighting.

Admiring the llamas who have hauled all the supplies to the Hopeless aid station

Got to finish before the final gun sounds at the finish at 30 hours

The inbound climb of Hope Pass is much harder. Having negotiated an average 15-degree incline gradient over 6 km outbound, the inbound climb has an average 20-degree incline gradient over 4km. Although shorter in distance, it is much more taxing and arguably the hardest section of the race. An approach that seems to work well for me in ultra running is “It’s better to be consistently good than occasionally great”. I just shift into my slow and steady pace which doesn’t require me to stop. I’ll always see people race ahead of me only to stop in a few hundred metres to catch their breath and then be passed again. I just like to grind away. Inch my way forwards and be consistently good. Stopping is not negotiable. Everything that can be done on the move should be done on the move. If you need to stop to breathe then you’re going too fast for your ability. At this point of the race, it’s a common sight to see athletes horizontal and keeled over their trekking poles as if they were figuratively ‘on the ropes’. Talking is minimal as breathing is hard enough as it is. Your heavy legs are balanced by your light headedness. As you break the tree line, there seems to be a never-ending series of switch backs which act like rolling upper cuts to your chin or solar plexus. When you see the multi coloured prayer flag markers at the top again, you know you’ve survived a stern examination of your finishing credentials. I take a moment to appreciate the view ahead of me. At the top of Hope Pass you can see Twin Lakes in the distance and Turquoise Lake in the far distance. Beyond Turquoise Lake is the finish line in Leadville. It’s hard to think that you were at the start line about 15 hours ago. Despite the nostalgia, I’m feeling pretty crap due to the altitude so I go up and over. I pass through the ‘Hopeless aid station’ staying well clear of the comforts of the warm fire whilst tipping my hat to the llamas. As I enter the tree line, the darkness starts to set in so I put on my head torch. The descent is quite challenging due to the rocks and recent rain fall so full concentration is required. Despite this, I descend reasonably swiftly and the drop in altitude feels so much better. It’s a continuous descent for at least 90 mins. I use my new found energy and keep running through the river crossing and lowlands all the way to the Twin Lakes aid station. The atmosphere at Twin Lakes is still electric which is uplifting. A kind gentleman dressed in a sumo suit offers to pace me but I politely decline. “Come on man!” he exclaims (I’m sure his offer to run the last 60km with me was in jest though I wasn’t prepared to compromise my finishing aspirations). I spend about 10 mins at Twin Lakes topping up my drinks and eating as best as I can. I put on some new shoes and dry socks which feel amazing. I manage to leave Twin Lakes at 9.05pm with a cumulative time of 17 hours and 5 mins and 55 mins ahead of the cut off time. I’ve heard that if you can leave Twin Lakes inbound within the cut off time, then you’ve got a good chance of finishing Leadville. By this point, about 40% of the field have already been culled. Despite being beaten up by Hope Pass, I’m in good spirits. The middle rounds of the fight have definitely gone to the Dreadville Slugger. However, the most important thing is that I’m still in the fight and I’ve managed to absorb arguably the worst the course has to offer. I asked Dr Stanley before the race that from his own study/appreciation of the course, which cut offs were the hardest to make from Twin Lakes inbound. “All of them” he replied. This run is relentless. Just got to keep jabbing and moving forward I guess.

View from the top of Hope Pass with Twin Lakes in the mid distance and Turquoise Lake in the far distance. Beyond Turquoise Lake is the finish line in Leadville.

Keen pacer ready to go at Twin Lakes

As I go up a rather nasty continuous gradient up Mt Elbert, the field is noticeably smaller though some runners have been joined by their pacers. The pacers are generally in high spirits and some are playing up beat music to keep their runners moving. Most of the pacers also seemed to be ahead of their runners in true ‘lead from the front’ style. I had arranged to meet my own pacer (Courtney) about 14km away at Outward Bound (the 123km mark) so I had good incentive to keep moving. Content to not drop my guard, I kept an honest pace throughout the night. Walking the ups, running the downs, and shuffling the flats. I don’t mind running at night anymore. It’s generally cooler and you tend to run slower so there’s less demand on the cardiorespiratory system. The main challenge therefore lies in staying focused and awake which is where caffeine, glucose, movement, and having company plays a role. Just before the Half Pipe aid station (114km), I was starting to lose focus and felt sluggish so I took caffeine tablets for the first time to help stay awake. I arrived at Outward Bound two hours ahead of the cut off time and slightly ahead of schedule at 1am. I linked up with Courtney who was kitted up and ready to go for her pacing duties. Courtney was keen to do the infamous “Powerline” section of the course which was the last significant climb and glancing counterpunch of the Leadville 100. I stopped briefly at the aid station to try eat something but by this stage of the race, its difficult to have any semblance of an appetite. Nibble and sip. Sip and nibble, I told myself as I tried to get more mashed potato and potato chips down. However, at the same time, I was acutely aware that I didn’t want to stress out my gut too much as a defunctioning GI system could be terminal. As Courtney and I left Outward Bound, I knew the road out of the aid station was runnable. However, the road also had a slight gradual incline (which was imperceptible in the dark) so I suggested that we walk out to give my stomach more time to digest my food and to ease Courtney into her pacing role. When we passed some fresh vomit on the road, I knew that we had made the right call. “Respect the gut” I told Courtney and she agreed. When we arrived at the base of Powerline, I asked Courtney to take note of the time. “This should take us 90 minutes” I told her. “There are lots of false summits. We just need to keep going for 90 minutes”. Still relatively fresh, it’s not long before Courtney powers ahead of me. I shout out to her and ask her to come back. “Just walk beside me!” I counsel. By the time you’re a 120km into a run, you don’t need a fresh pacer to motivate you to go faster and push the pace. I was in a fortunate enough position that I didn’t need to go any faster, I just had to keep going! I’ve seen instances where pacers have pushed their runners too hard. So hard that sometimes their runner can’t recover and they DNF when in reality they would’ve finished without their pacer. A good pacer keeps you company, reminds you to eat and drink, lights up the preferred route, keeps you positive, and unapologetically lies about how good you look. Thankfully, this is mostly what Courtney did. As we headed up Powerline together, in the still of the night, you could easily hear the electricity in the powerlines above you. It was a loud vibrant ‘crackling’. If I hadn’t been with others, I could’ve easily convinced myself that I was a sinewy, rancid, slab of meat that was slowly being cooked alive. When we finally got to the top of Powerline / Sugarloaf, we were greeted by the bizarre sight of an unofficial alien themed aid station dubbed ‘Space Camp’ with a large banner saying “Nice Fuckin’ Work!”. There were people dressed up in space costumes waving glow rings and someone blowing gigantic bubbles. I’d heard rumours that drugs were rife at this aid station so to be careful with what you accept or eat. Rather cautiously, I asked Courtney to fill up my drink bottle with WATER. Having never done drugs in my life, I didn’t think 24 hours into a 100-mile run would be a good time to start. I nervously shuffled past whilst Courtney lingered and enquired about the home made ‘performance enhancing’ cookies that allegedly could inspire “the best fuckin’ run of your life”. Heading down Sugarloaf felt as hard as coming up. By now your quads are cooked and your legs are sufficiently tenderised. I can afford little more than a shuffle. Hagerman Pass Road was smoother and less steep so provided a brief reprieve. But then you connect with the Colorado Trail again which is technical rocky downhill and hence so much slower at night. I discover that its easier (and safer) to walk quickly rather than jog. When Courtney and I finally reach Mayqueen, it’s just after 4.30am and still dark. “Make sure that you get to Mayqueen before sunrise” were the words of past finishers. The penultimate round was a points victory to the Molloys. We had 5 and half hours to get to the finish and were 2 hours ahead of the cut off time. I was exactly where I wanted to be. I had taken it deep into the race and the famous slugger was tiring. I could probably walk in from here and still finish. From here, it was my fight to lose.

Welcome to Space Camp at the top of Powerline

Leaving Mayqueen with the sun rising over Turquoise Lake

Leaving Mayqueen it’s like a great weight of pressure has been lifted. From here the strategy is simple. It’s 20 kilometres to the finish line. I’ve just got to keep going! Although the trail around Turquoise Lake was runnable 24 hours ago, in the dark and with tired legs, it feels impossible to run so we commit to a fast walk. Slowing from a shuffle to a walk, we start getting passed by those who are naturally fast walkers. “I don’t like being passed” Courtney tells me. “Let’s just walk briskly till we get to the Tabor boat ramp.” I tell Courtney. “Running in this stuff in the dark is hard work. From the boat ramp the trail becomes runnable again so we can start running then”. In the dark, you can just make out the shape of the lake as you chase shadows around the trail. Eventually, the dark becomes light and the sunrise brings fresh energy. Your depth perception returns and the trail becomes easy to see again. It was my turn to dictate matters and take the fight to the course. “Let’s go. We can run now”. When I say run, it’s not really a run but rather a shuffle. Runners can underestimate the effectiveness of a shuffle. Though a shuffle is a lot slower than a run, it is slightly quicker than a walk. And if you can shuffle, you will generally pass a lot of people on the way to the finish line. Courtney and I managed to shuffle all the way to the bottom of The Boulevard and passed a few people along the way as a result. My plan was to give myself at least an hour at the start of the Boulevard. “Don’t underestimate The Boulevard” I remember reading. I reached the bottom of The Boulevard with more than enough time to spare and 2.5 hours up my sleeve. The same downhill dirt road that you cruised along at the start of the race, is now a gradual painful incline all the way to the finish. The final body blow. Bordering on below the belt. Certainly not something I’d like to be running under time pressure 175km into the race. With the pressure relieved, I tell Courtney that my intention was to walk the last 5km to the finish. I share a story with her of a Leadville 100 runner who pulled out at the 98-mile mark as ‘he couldn’t go any further’. How is this possible? To endure so much and not finish so close to the end. Apparently his ‘body had shut down’. I had to remain vigilant. Keep my guard up. Control the fight all the way to the end. Turning off The Boulevard and onto West 6th Street, I knew that the fight was all but won. I knew every little contour and rise and fall of that street like the back of my hand. I can’t tell you how many times Dr Stanley and I had walked along this street at the end of every training run and ‘visualised’ this moment. And regardless of the distance run prior, Dr Stanley would always collapse over the finish line (only to non chalantly walk away after this – he is a very dramatic man). I’m over the last big rise next to the hospital and I shuffle down the final downhill. The temptation is to keep running all the way to the finish line. This is something I’ve always done. Finished strong. I think it’s become a self and societal expectation to cross the finish line running so I’ve done this every time. But after 99 miles at Leadville, I had nothing more to prove to myself or anyone else. For the first time in my running career, I actually wanted to walk all the way in. “I’m going to enjoy this one Courtney. I’m going to walk in. I want to savour this moment”. And so it was. There was still the adrenaline pumping noise but it was less of a blur and I could easily make out faces and smiles. I hug Courtney over the finish line. It was great to share a sunrise and the last 37km together. I’m not really a hugging person but now I’m getting hugs from Merilee Maupin and Ken Chlouber (co-founders) at the finish line and they give me my finisher’s medal and belt buckle. I’m thrilled to secure a clear points victory at the finish. It’s hard to beat an opponent who won’t give up. Motivation will get you to the start line. But only total commitment will get you to the finish. Dig Deep. Commit. Don’t quit. Inside each and every one of you is this inexhaustible well of grit, guts, and determination. You’re better than you think you are. You can do more than you think you can. Between the bang and the buckle, it’s up to you. Don’t dream of finishing an ‘A race’. Prepare for it. Train for it. Running is medicine.

Crossing the finish line with my wife and pacer Courtney

Leadville 2022 finishers (701 starters):

Andrew Stanley (NZ) 26:20:33 (108 of 368)

John Molloy (NZ) 28:16:52 (185 of 368)

You’re better than you think you are. You can do more than you think you can.

Ken Chlouber

Hugs all round at the finish line with Courtney and Merilee Maupin

Between the finisher’s buckle and you is a doughnut