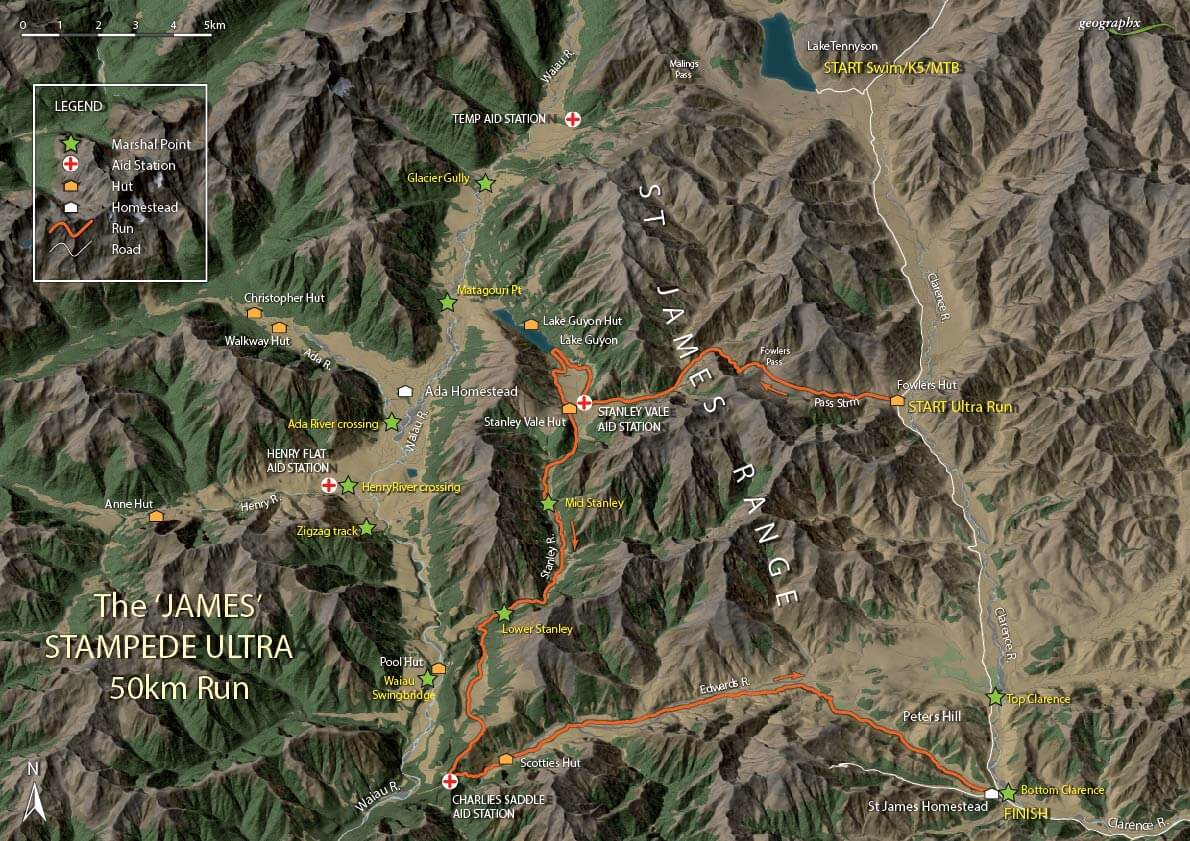

The “James” Stampede Ultra 50km 2022

Date:

January 22, 2022My Wife’s dietician: So what’s John up to this weekend?

Wife: He’s running an ultra one week after running an ultra.

Dietician: Why’s he doing that?

Wife: Because he’s an idiot.

I was really looking forward to participating in The “James” Stampede Ultra (50km). Mainly because I’ve never run in the St James Conservation Area before but also because it doubled up as good training for my pending Southern Lakes Ultra (300km run over 7 days) at the end of February. But as my wife Courtney is driving me down Tophouse Road just after 5.30am (a one hour stretch of gravel road to the start line), I’m beginning to wonder whether she’s right again. When we get to the start line at Fowler’s Camp around 6.30am, the sun is just beginning to rise and its quite crisp outside. The camp ground isn’t what I envisioned it to be. In the middle of nowhere, there stood a lone rusty tin shed (Fowler’s Hut) within a stone’s throw of a long drop. There is only one other competitor there and I’m beginning to wonder where everyone else is. After all, race registration was only 20 mins away at 6.50am and the race was scheduled to start at 7am. As Courtney drops me off, I thank her for her commitment and tolerance. She then turns around and heads back down the one hour stretch of gravel road back to Hanmer Springs again. Eventually a couple more cars arrive followed by a hire van which drops off a gaggle of runners. We all naturally gravitate towards the long drop and then into Fowler’s hut to shelter from the cold. Inside, the hut is very barren. There is one wooden table and on the wooden floor next to it, a sole bloke in his sleeping bag. Good God, I thought. This run is not for the weak. With only a handful of runners participating (<20), you invariably start chatting to a few runners. Tom from Christchurch is back for his third attempt at the ultra after coming second in his previous outings. He tells me that this is not the hardest ultra, but it’s probably the hottest. I ask Tom whether the first 4.5km to the top of Fowler’s Pass (1300m) is runnable and he responds in the affirmative. “There are a few sections on the course you’ll have to walk (as it’s impossible to run). But you shouldn’t have to walk the first bit.” He also mentions how it gets really hot along the long road back to the finish. “That’s the toughest bit. Last year when I crossed the finish line, I could barely breath as the air was so hot!” I then engaged in a brief conversation with a lady who was about as thin as the Fowler’s Hut door and must’ve been in her 70s. “I did this about 15 years ago so I figured I’d do it again before I get too long in the tooth” she mentions. I stand in silent disbelief. Sensing she was waiting a response; I finally blurt out “Good on you!” It’s almost 6.50am and there’s still no sign of the registration crew when suddenly the revving of a Land Rover breaks the morning silence. A portly couple promptly exit the vehicle and the gentleman drops the rear bumper revealing brown race packs. Wow. This is rugged man. There is a roll call and we all line up to collect our race numbers. The gentleman then begins a rushed race brief. Unfortunately, I was too preoccupied with my race pack and pinning my race number on that I didn’t catch much of the brief other than “Parts of the track are a bit vague.” And then, whilst still in group formation in the middle of Fowler’s Camp (i.e. middle of nowhere), he begins a countdown from 10 that ends with “On you go!”. And just like that, we all head towards the mountains.

At the start at Fowler’s Camp

The historic Fowler’s Hut

With Tom’s words in my head, I attempt to jog up Fowler’s Pass. However, it’s not long before I realise this approach is not sustainable. My body is still cold and my legs are heavy. Maybe with fresh legs running would be possible. But not one week after Kepler (not to mention my first run since). No way. My legs were simply not having a bar of it. I slow to a more comfortable walking pace and try ease into my run. With forecast temperatures in the high 20s / early 30s, I knew I had to start conservatively or risk being overwhelmed by the afternoon heat. Falling off the pace, I start getting passed by those who can still run when low and behold, the lady in her 70s glides past me! Oh. My. God. This is going to be a long day…

Although heat may actually improve performance in short duration activities (e.g. sprinting and jumping), long duration exercise is significantly impaired in heat. Research (predominantly conducted on marathon runners) has shown that the optimal temperature range for most runners is between 7-15 degrees Celsius. Outside of this range, marathon finish times tend to become slower on average. In fact, most world records and the top 10 marathon performances of all time have been set in temperatures between 10-15 degrees Celsius. So the most important thing you can do is adjust your expectations and your pace according to the environmental conditions. Exercise increases both metabolic heat production (your body is an exercising furnace) and the demand for blood flow/oxygen to your muscles. During exercise in hot conditions, your cardiovascular system has to not only transport blood to your working muscles, but also to your skin for cooling. The heat generated by your muscles can then be transferred to the environment and lost predominantly via evaporation (i.e. sweating). Importantly, as sweat reaches the skin, it must evaporate (i.e. transform from liquid to a vapour) for any heat loss to occur. This explains why exercising in humid conditions is extra challenging as sweat remains on your skin (a humid environment is already saturated with water so the last thing it wants is more of your water vapour). Which leads us to another important concept for runners to appreciate – ‘cardiovascular drift’. Cardiovascular drift is the phenomenon by which your heart rate increases to compensate for the reduced blood flow coming back to your heart (i.e. stroke volume) as more of our blood pools in the periphery to help cool us. As heart rate has been shown to correlate with your rate of perceived exertion (RPE), any ensuing increase in heart rate leads to an increase in perceived effort. RPE is arguably the most important thing that long distance runners are trying to manipulate throughout any run! Throw in some heat induced dehydration (which results in lower blood volume and a further rise in heart rate) and you can see why exercising in the heat is hard work! So, how can one optimise their exercise performance in the heat? The most important intervention one can adopt is to heat acclimatise. This requires training in the heat for at least 60min/day for at least 2 weeks. The risk of heat illness is greatest in early summer when participants are not seasonally heat acclimatised. The risk of heat illness is also greater in those who are currently sick or recovering from a recent viral infection (bear this in mind during Covid times). The other important element is hydration. Start any race euhydrated. Aim to drink 5-7mL/kg of fluid 4hrs before competition. In my experience, a 6-8% carbohydrate 750mL drink with dinner the night before is plenty. Any more and you risk peeing throughout the night. Hydration during an event should be individualised. This is best assessed during training with the most widely accepted method being monitoring body mass changes. Often hydration during an event is limited by fluid availability so if its going to be hot, know where your aid stations are. Although drinking to thirst is appropriate in most settings, if extreme heat or dehydration is expected, it may be beneficial to front foot your drinking requirements (sensibly). Finally, there is a role for cooling strategies in events but this is generally limited to those with die hard support crews. This can be done externally (e.g. cold-water immersion, iced towels/garments) or internally (e.g. ingesting ice or ice slurry beverages). If you’re still struggling in the heat despite all of the above, remember it’s okay to walk (and dare I say it, rest for a while if you need to and then carry on again).

Spectacular view at Lake Guyon

By the time I get to the top of Fowler’s Pass, I’ve definitely warmed up and am starting to feel lighter on my feet. I’m completely surrounded by mountains which have all been freshly painted by the rising sun. There’s then a pleasant descent back into the shade along shingle switch backs. The increased speed means I can really stretch my legs out and I’m back into my running groove again. As the gradient flattens out, the next section of the course is along creeks and small tributaries which eventually lead to multiple river crossings across the Stanley River. Alternating between muddy and wet feet become the norm. There’s then a detour to the first aid station at Lake Guyon (12km) and one of the most spectacular views ever. Fresh off seeing so many amazing views during the Kepler Track, I didn’t expect to get another “Oh wow” moment this soon. But I got one here. The lake was so calm and beautiful that it mirrored the mountains that surrounded it (the photo doesn’t give it justice). We then pass the historic Stanley Vale Hut and it’s back onto following the Stanley River again. Although it’s still early in the morning, the heat is really starting to pick up. I’m shoulder to shoulder with mountains again but there’s no hint of shade anywhere. The foliage in this region isn’t really conducive to shade and when it is, any respite from the sun is brief. I memorized that the second aid station was at 34km but I was starting to wonder where the hell it was. I thought that I’d been making good progress but this seemed like a very long 22km to the next aid station. I had banked on one litre of fluid to get me through. But now I was worryingly running short of water. The locals at the first aid station mentioned that I wouldn’t miss “The Racecourse” or the “the bums rush”. But to my knowledge, I hadn’t come across anything resembling a race course or any lost ancient Greek fartlek training group. Had I had missed something important in the pre-race brief? Had Covid changed their aid station quota? I could’ve topped up at any of the previous multiple river crossings but now I was beyond any fast-flowing tributary. Out of nowhere, nestled in some bush, I saw two elderly gentlemen (probably in their 60s) eating their lunch with their mountain bikes next to them. Somewhat surprised and hoping to garner some information on where the hell I was, I asked “How far to any civilisation?” To which they croaked “Oooooooooh miles.” I’d been told prior that there was every chance I’d see wild animals during this run (chamois, red deer, wild pigs, and native birds). But after my experience with my 70-year-old lady this morning and now these two chaps, I was beginning to wonder whether it was actually the elderly who were wild out these ways! Carrying on and after hours of shouldering mountains, the land suddenly just opens up. An openness so vast you could’ve probably put a race course on it. Ahh. The Racecourse. There is not a soul in front of me and I can just make out someone in the distance behind chasing me down. My happiness in reaching this landmark is short lived as the radiating heat from the sun smashes me from all directions. I push through along some very vague foot tracks until I reach a junction with an arrow pointing up a very dry hill side. This was the last thing I needed. I had minimal water left and I hadn’t anticipated another long climb. It was a very slow ascent up the baked ridge line following sporadic orange course markers. Eventually the ridge turned into subalpine bush with no visible tracks and more orange markers. Jeez, this is getting hard now. I take the dreaded last suck of my residual fluid knowing this final gulp would have to see me through to this ever-elusive aid station (and that’s if it even existed). In moments like this, I try not to dwell too much on the precarity of my situation. However, it’s very hard to ignore certain facts in life. In sports medicine, one of the early signs of dehydration is difficulty spitting. Right now, in the middle of nowhere, my mouth is dry and my saliva is thick. I dare not spit for fear of disrupting my psyche. I knew I had to transition from race mode to survival mode now. Nothing sharpens your focus like self-preservation. Moving to the top of the next feature, I see another elderly couple (probably in their 60s) admiring the view. What the heck is in the water here? I ask them if they’ve seen an aid station nearby. They respond that there’s something that appears to be an aid station at the bottom near the river. “How far away?” I ask. “About 1.5km.” “Ok, I can handle that” I respond.” But it’s about 2000m down” the gentleman adds. I must’ve looked worse for wear as intuitively the gentleman then followed up with “Why, are you hurt? “No, I’m just out of water” I replied. “Let me give you some. Let me give you some” he fretted. “You won’t last long in this kind of heat.” I was really taken aback by what followed. The couple then preceded to top up my 500mL water flask. “I only need half” I shamefully mention. “No, no, no, I’ll fill it all the way up. We got this from the river. We’re staying in the hut tonight so we won’t need this all.” Who would’ve thought that an act of kindness was as invigorating as the water itself? I instantly drink half the flask and with that, I’m back in the game. After the next high feature, I can make out a white tent at the bottom near the road. Finally the aid station! The descent down followed no tracks and was pretty steep. I thought that I was doing pretty well to hold my feet until near the bottom, when I suddenly slip and come crashing down onto my rear end. Ahh. The bums rush. I was pretty ecstatic to make the aid station but I was also pretty mentally fried by now. “Wow. That was a hard 34km!” I exclaim. Once there, I take as long as I need. I easily drink another 500mL and fully top up my water flasks. As I leave the aid station, I remember Tom telling me that the long road back to the finish in the heat was the hardest. Sixteen kilometres to go. I can do this. For the next couple of hours, it’s a lonely battle against the straight road and the heat. It’s not until I reach the final aid station at 44km that I bump into another runner. We turn off the 4×4 track together and it’s a short sharp climb through bush into Peter’s Valley and I’m surrounded by mountains again. It’s scorching hot during the final push to the finish at St James Homestead. I’m relieved to see my wife and 6-year-old, Millie near the finish line. I cross the finish line around 2.30pm with a finish time of 7 hours and 26 mins. I’m toast! I gravitate towards the shade of the pine trees to catch my breath. Millie runs towards me appearing super excited. “Can we go to Hanmer Springs now Dad?” she asks. “The kids have been waiting all day to go for a swim with you” my wife quips. I pause for a bit. I’m not sure if I can handle this. “Sure Millie. Let’s go.” “There’s no way I’m going in the heated pools though” I whisper to my wife. Running is medicine. Join me at my next blog, The Port Hills Ultra (50km) at the beginning of February.

Heading towards the finish line with Millie in support