Great Southern Endurance Run (GSER) 112.5 miles (181km):

100 mile # 1

Date:

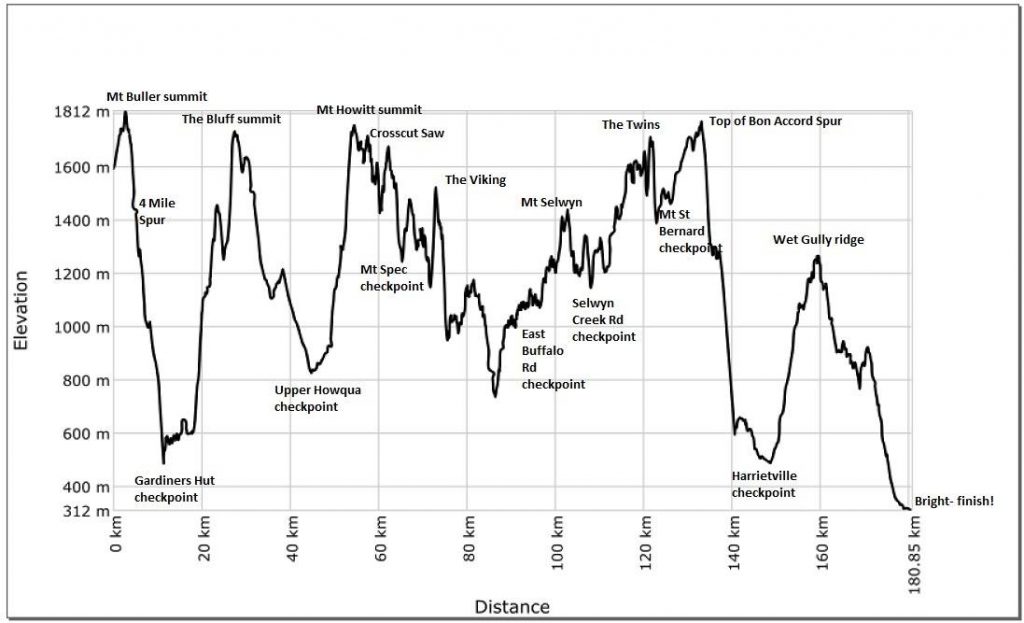

November 17, 2017The Great Southern Endurance Run (GSER) is a point to point 100 miler which starts in the ski town of Mt Buller and finishes in the small township of Bright. The race is predominantly run in the Alpine National Park in the Victorian Alps about 2.5 hours drive from Melbourne. This year was the inaugural running of the GSER and it was also my first attempt of the coveted 100 mile finish – the holy grail of ultra endurance running. The course is actually 181km long which is 21km longer than a standard 100 mile race (160km). With a total ascent and decent profile of 10 000m and 11 000m respectively, this promised to be seriously brutal. Despite running more than 70 marathons and five 100km races, the thought of the GSER still terrified me. Like most things, it seemed like a good idea when I entered a year ago. One year on, and it felt like I had the weight of the Victorian Alps on my shoulders. This would be suffering on another level. A hurt box without a key. I had never run through the night before (who does that?) I had also never had a DNF (did not finish). Like most of my previous events, I followed my simple philosophy – Just get to the start line and treat the start line with respect. It takes a lot of courage to enter. It takes even more to get to the start line. In the dark with our head torches on, more than 150 runners lined up for the Friday 5am start. All our hopes, fears, and dreams at the start line. Willing to challenge and daring to believe. Time to enter the hurt box.

At the start line of the inaugural GSER 2017 with Dr Rich Newbury (left) and Dr Andrew Stanley (middle)

I set off with my two good friends, Dr Andrew Stanley and Dr Rich Newbury. Hopefully we would run most of the run together. I knew things would eventually get tough and misery is better shared. It was a crisp start as we ran through remnants of snow on Mt Buller (1800m). Soon we were treated to our first sunrise and a steep descent down 4 Mile Spur. In this short 11km section, we got a taste of what we were in for. The terrain was single track and technical. Keeping your footing on the steep slippery descent was challenging. The track was also overgrown and arguably non-existent in areas. You would be comfortably running along and next thing you know, the track would disappear. Looking out for the course orange markers became extra important. The rocky spur section really slowed Andrew and Rich down. They had already taken a few falls (blood had been drawn) so they were running extra cautiously. Falling saps your energy and confidence. In ultra running, confidence is currency. My persistence with using trekking poles over the last four months and my recent purchase of good off road running shoes was really paying off. I had kept my feet throughout whilst others were losing theirs. We arrived at Gardners Hut aid station at 7.50am, just before the 8am cut off time. Somehow the first 11km had taken us 2 hours and 50 minutes. We were hoping to maintain a 43 hour finishing pace but at this pace, our expected finishing time was around 53 hours. I wasn’t overly concerned by our slow progress. I’ve learnt previously that for every minute you gain at the start of a race, you lose 10 minutes at the end. Ultra distance races are more often lost in the first 11km rather than won. The next section from Gardners Hut started off pleasantly alongside a beautiful flowing river. The smell of eucalyptus was distinct and refreshing and a choir of Australian birdlife filled the bush. We then climbed our first real ascent up Eight Mile Spur. As we hiked upwards, the grumbling of thunder in the distance became more prominent. It unnervingly became apparent that the interspersed charred trees were remnants of previous lightning strikes. Nature’s cigar I thought. Surely lightening wouldn’t mistake me for a victory cigar? As the forecast rain set in, the climb became more taxing. The rain turned the normally dry dirt to mud, and water began to flow down the track. As we approached the Bluff summit, things began to get nasty. Thick mud was replaced by a vertical rock cliff face which involved some serious scrambling. I never thought the GSER would involve rock climbing! On reaching the top, the cloud and rain ensured there would be no views this time. During the descent, I ran with Rich along the bush track and then with Andrew for the remaining section of forest road. We all arrived at Upper Howqua aid station (cumulative distance 45.5km) around 2.45pm, fifteen minutes before the 3pm cut off time. This was not the welcome relief we had hoped for. The race organisers had made this a ‘hard cut off’ so we also had to vacate the aid station by 3pm. I hurriedly ate my noodles and changed into a dry pair of socks before taking off again. The pressure to make the cut off times was beginning to take its toll.

It became apparent early on that formed tracks would be a luxury

The next section from Upper Howqua to Speculation aid station was 17.3km long and we had 5 hours to complete it. There were several river crossings so I enjoyed my dry socks for a total of 5 minutes. As we began to climb, I pulled away from my friends again. I was surrounded by mountains everywhere I looked. The descent from Mt Howitt summit was probably the high point of my whole race. The rain had cleared and the wind was still. The sun was approaching the horizon and was within touching distance. I ran through an open area of purple alpine flowers as far as the eye could see. In this moment, I was truly grateful for the gift of running. That gratitude seemed to spread to every part of my body. It was a powerful feeling. At the same time, I felt like a fragment of insignificance passing through such a vast alpine environment. These are the moments we cherish and run for. As I ran along the Cross Cut Saw (13 spectacular peaks and saddles/teeth), the weather began to take a turn for the worst. It started to rain again and the wind began to pick up. The thunder sounded more ominous and the flashes of lightening too close for comfort. We had received a text earlier in the day from the race organisers warning us of thunderstorms. It advised us to avoid high ground, and if this was not possible, to lie flat. Are you serious? By now I was about 1800m above sea level and there were quite a few peaks in front of me. I also had a cut off time to make and lying flat was unlikely to help with this. I was hoping Andrew and Rich would have caught up to me by now but they hadn’t. The grumble of thunder turned into a loud crack of a whip and hail began to fall. There was no holding back now. For the next hour or so, I ran on fear and pure adrenaline. Each thunder clap spurred me forward. I ran faster on the peaks, visualising the charred trees I had seen earlier. Up Mount Buggery and along the Horrible Gap. When the thunder storm passed, the sun came out again as if nothing had happened. It had a calming effect on me and I eased into a more sustainable pace. The track towards Mt Speculation was grossly over grown and before long, I was bush bashing again. The overgrown track to Speculation aid station seemed to take forever. The sun was starting to fade and I hadn’t seen anybody in a while. As I don’t run with a watch, I had no idea what the time was. When I finally arrived at Speculation aid station (cumulative distance 62km), the station was deathly quiet. The check point looked like a last chance saloon. There was an ambulance next to a small marquee with only one runner wrapped in blankets with his head torch on. I asked a guy who looked like a volunteer what the time was. He told me it was 8.20pm. My heart sank. I knew the cut off time was 8pm. How on earth had the last 17km taken me more than 5 hours? He asked me what race I was doing, the 50 or 100 miler? I responded the 100 miler. He replied that I was 20 minutes over the cut off time and would be unable to continue. I was rather annoyed but held restraint. “But the cut off for the next check point is not until 6am. I’ll easily make that” I said. He responded that the cut off time was actually 9am and not 6am which made me feel even more desperate. He quizzed me if I was carrying an injury which annoyed me slightly. I responded, “No, I’m trying to pace myself for a 100 miler and this is a bloody tough course!” I knew rules were rules and this poor chap was just trying to do his job. “Ok, if that’s the way it is, that’s fine” and I sat down. I’m sure that I looked and stunk of defeat. I guess I just had to wait for Andrew and Rich now. The run so far had been incredibly tough going and I had just been given the key out of the hurt box. Just as the initial disappointment gave way to a sense of relief, the same guy returned and said, “I’ve had a chat with the tail end Charlie and he is happy for you to continue”. Talk about an emotional roller coaster ride. All in the space of a few minutes. Like a bolt of lightning, I was up again. However, I wasn’t in great shape and badly needed a running makeover. I asked if they had any noodles but was told they had run out. Great, there goes my dinner I thought. I went about getting changed into new running clothes, socks, and shoes when another competitor called Chris from Sydney arrived. He too was doing the 100 miler and was also told that he was over the cut off time. I could sense the conundrum that I had created. To which another volunteer lady quickly rectified by saying, “Look, if you two get out of here within the next 5 minutes, we’ll let you carry on. If not, it’s the end of your race. But you’ll have to go together.” That made us move real fast. Chris and I introduced ourselves. Within minutes, we had left Speculation. I thought of my friends, Andrew and Rich. Would they let them pass too? To the distant grumble of thunder and with the sun setting behind us, Chris and I headed into the darkness. I realised that I was back in the hurt box again and had just thrown away the key. I had never met Chris before. But I sensed, like most runners I knew, that he seemed like a good person. “John, I’m so glad to be running with you tonight.” It was a nice touch in a day full of carnage.

Feeling lost? You’ll be fine. Just follow the orange markers. Yeah right.

I’ve never run through the night before. My preference is to sleep at night. I’d come close to doing all nighters back in my youth. This typically involved a New Year’s Eve surrounded by women and alcohol but usually I’d succumb to one or the other. Running through the night was one of my fears before the race. It was a great fear of the unknown. Night navigation can also be extremely difficult. I was worried that I would get lost and stranded, or somehow go in the opposite direction and end up back where I started. Thankfully, Chris had run three hundred milers previously so he had some experience with night running. As we began to talk, Chris mentioned that the race organisers were known in the local area for creating tough events. He told me that the GSER was the 5th hardest ultra in regards to total elevation and descent profile. The race organisers had expected that 70% of starters would not finish. Next year, the race organisers hoped to run the race in reverse so it would become the 3rd hardest ultra. This was all news to me. I’d entered purely so I could run with my friends who were now gone. “I’m not coming back next year” I responded. I spent a large portion of the night angry. Why make a course where you want the majority of people to fail? The cut offs seemed too tight and established runners with good pedigree were being picked off. Surely, if you meet the pre run entry criteria, then you should have some hope of finishing? It was also one thing to make a course hard, but it’s another to actually mark the track. The night course was brutal. I had never experienced anything like it. Keeping on track was difficult. To be honest, for large sections, there was no track. We simply had to follow spaced out orange markers through gaps in the bush. Bush bashing was the norm. Many fallen trees blocked our path so I had to contort my body to either go through, over, or under the fallen debris. I was glad my many years of yoga had prepared me for this. We passed one runner sitting on a fallen tree. He looked defeated. His mind was sound but his body was protesting. “I’ve done 5km in 5 hours” he said. That was how slow we were going. The night was long and hard. We negotiated Mt Despair and went up The Viking. The Viking was horrendous. Once again, we were scaling rock cliff faces. The only direction was up. Someone had installed a quarter ladder and climbing rope at one section. It was probably the scariest part of the whole course. It required climbing up a miniature ladder with a rung just wide enough to fit the width of your shoe. You then had to squeeze between a rock face and a branch (the latter having a tendency to snag your back pack) before hauling your body up a climbing rope. At one point, my whole body weight and life was dependant on my left forefoot which was beginning to cramp. I somehow managed to get myself and my trekking poles up. I then took hold of Chris’ pack and poles so he could climb up. When we had both reached top, I was genuinely grateful to not be paralysed! If I was angry beforehand, now I was fuming. I had another moan to Chris about race safety and asked how it would be possible to evacuate anybody from that position? Chris seemed to calm me down somewhat. It was reassuring to know that he had run through the night before. “Think positive and keep eating and talking. Next thing you know, the sun will be up” he counselled. Despite all the anger and despair, what transpired that night was friendship. Throughout the night we exchanged conversation, rotated navigation responsibilities, and sat down and shared meals together. I was happy to be with someone else. Misery attracts companionship and GSER was handing out buckets of it. Eventually the sound of night birds was replaced by the sound of day birds and the sun began to rise. I could feel my body re energise as the sun began to peak over the mountains. As much as I wanted to keep running with Chris, I felt an urge to push forwards to ease the cut off pressure. We had run together through the night as directed by the stern volunteer lady. I felt like I had honoured my part of the deal. I expressed to Chris my desire to push onwards and we shook hands and wished each other luck. For the next hour or so, I felt recharged and was running strong. Then suddenly, I began to burst out crying. I was alone again. My friends were gone. I had been running all day and night. Now, I had to run all day again. It was all too overwhelming. They weren’t tears of joy or sorrow. I think they were tears of confusion. What the hell was I doing? When you run, you feel more. You ride waves of emotion. This was raw emotion. I had nothing to hide. No fear of judgement. It just needed to come out. I eventually composed myself and managed to pass three other runners on the way to East Buffalo Road aid station. I arrived at East Buffalo Road (cumulative distance 94km) at about 7.45am. I had been running for a total of 26 hours now. I had hoped to arrive earlier while it was still dark so I could sleep. But as the sun was already up, I decided to stay awake and concentrate on refuelling for the day ahead. I asked for noodles but again they had run out. I stomached a protein shake, cheese bread, and hash brown, and then pushed on towards Selwyn Creek Road.

Buggery, Horrible, and Despair. The elevation profile of the 5th hardest ultra.

As I left East Buffalo Road, I took a moment to plan out my day. I was going slower than planned. Before the run, I had mentally prepared myself to run through two sunrises and two sunsets. At his rate, I had better prepare myself for three sunrises. My heart sank a little. I prepared my day’s to do list. 1. Stay upright. 2. Move forward. 3. Don’t black out. That seemed sufficient at the time. The majority of day two was a bit of a blur. I knew I had to get to Mt Saint Bernard aid station where our lone support person, Jamie, had initially agreed to meet Andrew, Rich, and I. We hadn’t established an order of priority but I assumed it was me now. Maybe Andrew and Rich would be with her? Maybe Andrew and Rich were actually behind me. I had no idea. I had to focus on moving forward and that’s what I did. After last night’s terror, I knew I had to make hay while the sun shined. In the hot Victorian sun, I ran/walked along undulating bush, up Mt Selwyn (I was too tired to appreciate the views), up a good road with a mongrel hill, and arrived at Selwyn Creek Road aid station by midday (cumulative distance 108km), one hour before the cut off time. The volunteers at this aid station were the best so far. They were overly helpful and enthusiastic. I was offered a hot chocolate and fed off their freshly cut fruit and enthusiasm. As tempting as it was to stay, I was driven to create as much time between me and the next cut off time. I was in too deep now. I couldn’t afford to become another casualty and was determined to finish. I gave thanks to the volunteers and paramedics and left Selwyn Creek towards Mt St Bernard. Before leaving, I was warned that the next section was ‘quite a bit harder’ than the previous section. I had about 6 hours to cover 16.8km so was reasonably confident. The cut off time at Mt St Bernard aid station was 6pm. Hopefully, if I got there early enough, I could afford a short rest and a change of clothes. It was during this run section that I was lucky enough to meet the A team – Adrian and Adam. We had played cat and mouse during the previous section. They moved faster than me but tended to rest more so I would catch them during their breaks. They were an interesting team. Adam was an Army engineer and Adrian had a fear of falling. How he had got this far was beyond me! The A team were magical at spotting orange markers and worked beautifully navigating as a team. My short sightedness was a weakness so I hung on behind them as hard as I could. They seemed content to let me follow in their wake. Any road cyclist would have dropped me by now. Over, through, and under more fallen trees. Along scrub and rocks. The A team stalked one orange marker to the next. By this point of the race, I was really starting to struggle. To use a boxing analogy, the GSER had me on the ropes and I was in trouble. Not having to navigate conserved energy. I simply followed the A team. I don’t think I could have got through this section without them and for that I am grateful. The final section to Mt St Bernard was an introduction to ‘The Twins’. A 1700m almost hump-backed mountain. ‘The Twins’ were the one-two sucker punch. From a clearing in the bush, emerged a trackless mountain side with a string of orange markers going directly up. There was no peak in sight. If I was a man at the bottom, then I was a carcass at the top. The reward for reaching the top? A galling descent down the other side of the trackless mountain side. I somehow managed to roll with the punches albeit being punch drunk by now. I arrived at Mt St Bernard aid station (cumulative distance 125km) at 5.45pm, 15 mins before the cut off time and in serious damage control. The time buffer I had created earlier in the day had been obliterated by ‘The Twins’. I was so happy to see Jamie, Andrew, and Rich at the aid station. I had so much to tell them and many questions to ask. But I was in a huge panic. The cut off times had picked off many a proud runner and it now had a huge bull’s eye on my back. I had been craving noodles for more than 24 hours so I asked if there were any noodles again. Negative. Great, no noodles for dinner again. I had enough time to change into a new pair of socks, swallow a hash brown, take one bite of my 6 inch Subway, and swig some fresh cool orange juice before taking off again. Rich ran with me for a bit down the road. He explained how they had not arrived at Speculation check point until after 9pm so could not continue running. I spoke about my tears of confusion and how I had grave fears for the night that lay ahead. I asked if he’d consider pacing me at night. I expressed my doubts about safely navigating at night in my current mental state. He said that he’d think about it. I thanked him for considering and pushed on to the final check point before the finish, Harrietville.

‘The Twins’ a.k.a. the ‘one-two sucker punch’. Looking back at one summit from the other.

When the sun began to set for the second time, things started to get hard. I had been running for more than 36 hours now without sleep. The melatonin was building as I pulled out my night light for the third time. I met up with the A team again. They had a fresh pacer for this section (oh the luxury). Adrian and the pacer attempted to ascertain my life story. I politely answered when I could. The reality was, I was finding it hard to keep my eyes open, yet alone speak. I was on the ropes again. Just clinging on. I marvelled at their ability to talk. I mentioned that I had not had the chance to sleep as I had been chasing cut off times all day. They shared their favourable experience with short 20 minute sleeps and recommended that I give it a try. I agreed that I’d give it a go at Harrietville (if I hadn’t already blacked out my then). Although running at the tail of a group can be helpful, I was finding it quite difficult this time. The combination of talking and adjusting to dazzling reflective light from the safety vest ahead was draining my limited energy stores. The need to be both ‘reflexive’ and ‘responsive’ to the lead person (and ensuing swinging branches) was also too energy intensive. When Aaron had to stop for gastrointestinal issues, I knew this was my opportunity to run my own race. I explained that I would keep walking and I was sure that they would catch up to me. After a time walking, I managed to build to a jog. From a jog, to a nice canter. By running by myself and at my own pace, my brain switched to auto pilot. I began to feel better again. In the cool of the night, I descended swiftly down Bon Accord spur and towards Washington Creek Junction. I crossed the damaged wooden bridge and ran along the river. The A team never caught up to me. Time seemed to fly and 21km later I arrived at Harrietville (cumulative distance 146km) at 11.30pm. By now I had been running for more than 40 hours so I was keen to have a sleep. The race organisers had factored up to 4 hours sleep at this aid station and the longer 3am cut off time reflected this. However, by this point, I had lost all faith in the race cut off times. Making prior cut off times never guaranteed that you would make the next, so I intended to leave well before 3am. I began looking for Jamie, Andrew, and Rich, but was instead greeted by the race organiser, Mel. She was incredibly kind and helpful. On the A team’s advice, I asked Mel if I could sleep for 20 mins. She made me a hot chocolate and reassured me that she would set an alarm for 20 mins. I’m not sure whether I slept or not but when I was roused, my head space felt better and I think my body appreciated staying still for 20 minutes. When Mel asked if there was anything else I wanted, I sheepishly asked for noodles. When she replied “Sure thing”, a sense of euphoria filled my body. I’d only been craving noodles for the last 30 hours! I gratefully finished them and then tucked into some salted boiled potatoes. The A team eventually arrived at the aid station whilst my support crew were nowhere to be seen. Where were they? I’m sure sleeping in a warm bed would’ve been more appealing. However, I dearly craved the company and I was still apprehensive about navigating by myself at night. When it became clear that my night pacer wouldn’t be coming, I asked the A team if I could join them again for the next section. Adrian agreed and we left Harrietville that night at 12.30am. We had 34km to the finish and 9.5 hours to complete it in. The event organisers had predicted that a ‘slow runner’ would do this section in 7 hours. I had proven myself to be slower than a slow runner in all sections of this course to date. We left the outskirts of the town where a lone elderly gentleman cheered us on. He asked us how we were feeling. I responded positively by saying that I felt like a new man. In reality, I was only feeling a fraction of my true self. We then headed deeper into the darkness and the unknown.

Feeling worse for wear at Mt St Bernard aid station (cumulative distance 125km)

It didn’t take me long to realise that I wouldn’t be able to stick with the A team. They must have taken some serious performance enhancing agents as they were walking like men possessed. I pulled out my race map which showed a total ascent of 1300m and descent of 1500m for this section. This pace was suicidal. I told the A team that they were going so fast that I could not think. I had to slow down as I needed all my wits about me tonight. We wished each other good fortune and I eased into a more comfortable pace. I was commander and chief navigator now. I spoke the words of my late father – “If it is to be. It is up to me.” I had to be courageous. I had to face my fears. I needed a sharp mind. Unlike the previous night leg which involved bush bashing, going over and under fallen trees, and scaling cliff faces, this part of the course was completely different. My map had two significant features – “High Point” and Wet Gully Track. For some reason, I had expected thick bush and the possibility of wet feet. What eventuated was a form of race organiser sick torture. We remained on a fire trail throughout. Although constantly looking for orange markers to navigate can sap your mental energy, at least it kept you alert and awake. This section had sporadically placed orange markers. After what was probably a couple of hours, it became clear to me that there was no requirement to navigate. We would simply keep going along this fire trail until we were bored to death. A form of slow torture. The only thing you saw was the dry dirt in front of you, and the only thing that changed was the gradient of the road. If I thought that my first all nighter was hard, the second was a brutal game of trying to stay awake. The glucose and caffeine that had served me well during the first night, was having no effect at all tonight. Melatonin was flooding through my system and I was drowning in it. I was a zombie who was walking myself to sleep. I knew sleeping was not an option. As tempting as it would’ve been, I feared I would’ve fallen into a deep and unarousable sleep. I’d surely make the morning newspaper headlines – “New Zealand man found 25km from finish line lying in fetal position hugging wombat.” I took more glucose and ate more food but nothing seemed to help. I poured my water bottle over my head and splashed my face, but this only startled me temporarily. As the gradient began to flatten off, I realised I had to run. My god it hurt to run but surely the pain would keep me awake? And so I began to run. And when I passed another runner whose headlight seemed unpassable for hours, I got a sudden burst of energy. Eventually, I passed the A team again. Running and passing people seemed to be working. Before long, I was alone again. Despite running, it was still a struggle to stay awake. It became clear that I had to add another treatment. I had no one to talk to so singing seemed appropriate. So I sang loudly. Loud enough to keep me awake. I didn’t care if anyone heard me. I was already a dead man in my view. Like a repeating karaoke, I ran and sang along to the Beatles (Let it be), Tina Turner (Simply the best), Peter Andre (Mysterious girl), and the chorus of R Kelly’s ‘I believe I can fly’. Somehow I did this until I saw my 3rd sunrise. With the sunrise, I felt my body reawaken. There was no further requirement to sing. I was back in the fight again. Race distances had been posted every 5km throughout the course. I must have missed a few during the night, but in the day light, they became visible again. From about 170km onwards, I began to hallucinate. It was bizarre as I knew I was hallucinating. The images were very real but in pixels of green. They mainly consisted of wild life crossing in front of me, my own crowd of supporters (to make up for the lack of GSER supporters), and vehicles reversing in front of me and then driving away. My favourites were the running man, delicately poised in the middle of the track before taking off and leaving behind his shoe; and the neatly placed table and chair set right in the middle of the track which conveniently disappeared as I got closer. At the time, I thought they were rather amusing. It is only now that I realise I was actually in a pretty bad state and that my hallucinations were most likely the side effect of my very own self-induced general anaesthesia and morphine. By this point in the race, every small incline felt like a mountain. I was staggering and swerving sideways. Dismantling and veering out of control, I could no longer run. The sun was well and truly up and I began to panic again about cut off times. When I hit the 175km mark, I felt defeated. The last 5km from 170km seemed to take an eternity. I hit my first major wall. For the first time in the whole race, I thought that I couldn’t finish GSER. I’d already achieved 100 miles (160km) but the last 21km of this race was barbaric. I thought, “How could I finish the last 6km when I could hardly walk in a straight line for 10 metres?” I stopped and sat down only to receive a sudden urge to pass a bowel motion. Great, I was not in the mood to connect with nature again so I had to keep walking. I needed to know what the time was but my mobile phone was flat. I took out my accessory battery charger and started charging my phone. When my phone eventually turned on, it was just before 7.30am on Sunday. The probability of going to church today was diminishing. The finish line cut off time was 10am so I had 2.5 hours to do the final 6km. It seemed achievable on face value. But at that moment and after 175km, it seemed impossible. I sent a text to my wife – ‘Not sure if I’ll finish. Need to do 6km by 10am. Can barely walk.’ That was my SOS. I put my phone away and kept walking. It was all my body would allow me to do. I had to hold on. I had to sustain. Everything hurt by now. The only part of my body which felt reasonably comfortable were my eye brows. I concentrated on walking with my trekking poles but even my arms were starting to give up. I kept moving forward albeit slowly. Suddenly, the bush began to open up. There was a gentle descent which didn’t burn my quads so badly. I used the momentum of the hill and somehow managed to get back into a jog again. I saw a house in the distance and cars driving along what appeared to be a highway. As I approached the house, I looked towards it and saw a lone figure in pixels of green. He was standing by the front door saluting me – ok, real house but still hallucinating. As I ran down the country road, what I saw next filled by heart to the brim. Even better than the noodles at Harrietville. My wife had obviously rustled up my support crew and I recognised our rental vehicle driving towards me. Jamie was driving and Andrew and Rich got out and started running with me. They explained that they had set their alarm expecting to see me at Harrietville at 3am. They had therefore missed me completely. It didn’t bother me as I was simply relieved to see them again. My night pacer had finally arrived to see out the last few kilometres in the morning! Andrew gave me my favourite tonic – cold orange juice straight from a 2L bottle. I was immediately reenergised. Something magical happened soon after. One of the most powerful feelings you can ever experience – I can, became I will. It was time to deliver my own knockout punch to GSER. Andrew and Rich escorted me until the finishing arches were in sight. It was time for this to end. After starting at 5am Friday, I crossed the finish line just before 8.30am on the Sunday. 51 hours and 25 mins later, it ended. The walls of the hurt box disintegrated and I was free. One hundred and fifty runners started the GSER. By the time the race had officially ended, only about 50 runners crossed the finish line. The casualty rate was high but the reward was greater. That day, in that small township of Bright, I found my hero. And that hero was me.

On the home stretch with my ‘night pacers’

In our lives, we plant seeds every day. Sometimes, we don’t even know we are sowing seeds. When you leave your front door and go for a run, you plant a seed. That seed grows into a 5km run. My first marathon planted a seed for my first 100km run without me knowing it. My first 100km run planted a seed for my first 100 miler without me knowing it. Over time, seeds grow. Sometimes they need a bit of nurturing and encouragement. Others are stubborn and need to be challenged to grow. If it doesn’t challenge you, it won’t change you. Life can be monotonous. We still need to hang our laundry, cut our lawns, and vacuum our cars. Running allows us to break this cycle for a temporary moment. It allows us to dream. When you dream, you sow seeds in a field so large it is beyond imagination. I urge you to make your start lines. Chase your dreams. Face your fears. Find your hero. Running is medicine. Join me at my next blog, Honolulu marathon, 3 weeks post GSER.

Crossing the finish line of the inaugural GSER 2017 in Bright

I have found my hero, and he is me.

Dr George Sheehan, Cardiologist